BM(Hons) MD FRCS(Neurosurgery)

Consultant Neurosurgeon

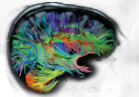

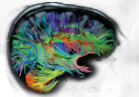

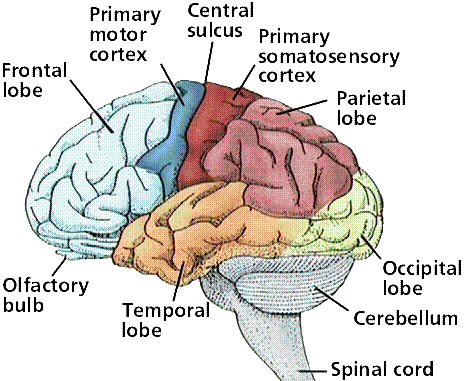

The brain is a complex structure containing millions of nerve cells (neurones) and their processes (axons and dendrites) in a highly organised manner and supported by many other cell types (astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, etc). The brain is divided into several regions that have different functions: the cerebrum is the largest area and is divided into 2 cerebral hemispheres. The cerebellum is situated beneath the cerebral hemispheres and is connected to the brainstem, which in turn runs into the spinal cord.

The left and right cerebral hemispheres control functions for the opposite side of the body. In addition, certain important functions (particularly speech and language) are located in only one hemisphere, which is then termed the dominant hemisphere. In right-handed patients this is virtually always the left hemisphere and in left-handed patients it may be either hemisphere (but is still often the left).

Each hemisphere is divided into 4 principal lobes that can be seen on the diagram and a hidden small lobe called the insula. The surface of the brain is folded with each crest being termed a gyrus and each groove between them a sulcus. The central sulcus separates the frontal from the parietal lobe and on each side of this sulcus lie the pre-central gyrus (in front) and the post-central gyrus (behind). The pre-central gyrus (motor cortex) is responsible for movement on the opposite side of the body and the post-central gyrus (sensory cortex) is responsible for appreciation of sensations.

Control the movement on the opposite side of the body predominantly via the pre-central gyrus. In the dominant hemisphere the lower region of the frontal lobe immediately in front of the pre-central gyrus controls the expression of speech. Damage to both frontal lobes may produce an alteration in personality, a loss of normal inhibitions and incontinence.

Control the appreciation of sensation from the opposite side of the body largely via the post-central gyrus. In the dominant hemisphere the lower region of the parietal lobe plays an important role in the understanding of speech and language and performing calculations. Nerve fibres from the optic nerves (controlling vision) pass deeply through the parietal lobes to eventually reach the occipital lobes.

Control vision from the opposite visual field. Damage to one occipital lobe would produce a deficit in vision that would effect the visual field in both eyes, making it difficult to see peripheral objects in one direction only. It would not cause blindness - this would only be caused by severe damage to both occipital lobes.

The temporal lobes play an important role in memory with the dominant side being more important. However, it would often require damage to both temporal lobes to cause a severe memory disturbance. The upper portion of the temporal lobe on the dominant side also plays an important role in the understanding of speech and language, along with the adjacent parietal lobe. Nerve fibres from the optic nerves (controlling vision) also pass deeply through the temporal lobes to eventually reach the occipital lobes.

Controls coordination in the limbs and the trunk by receiving information from sense organs via the spinal cord and input from the cerebral hemispheres. Damage here may impair coordination of limb movements and cause unsteadiness of gait.

All nerve fibres connecting the cerebral hemispheres with the cerebellum and spinal cord pass through the brainstem, controlling all functions in the limbs and body. There are also collections of neurones (nuclei) in the brainstem that control many functions in the head and neck, particularly eye movements, facial sensation and movement, swallowing and coughing. Areas within the brainstem also control consciousness, breathing, heart rate and blood pressure. As these vital nerves all lie very close together in the brainstem, even a small area of damage might produce multiple severe deficits.